Irish directors are tasked with high stakes work health and safety duties under current legislation. However, there is little guidance available to inform those individuals of the practical steps they can take to comply with their statutory duties. Aoife Gallagher-Watson from the international labour, employment and safety team at Seyfarth Shaw considers how guidance can be taken from other common law jurisdictions.

Directorial responsibilities for health and safety at work

Under Irish work health and safety (WHS) laws, company directors can be held personally liable for work place health and safety breaches. When faced with allegations in a WHS prosecution, the reverse onus jurisdiction sees directors charged with the onerous task of proving their innocence by demonstrating to a court that they carried out all that could be reasonably expected of them in accordance with the requirements of the Health and Safety Act 2005.

Current legislative guidance

Despite the serious repercussions for a breach[1], the legislation provides little guidance on how a director might uphold his/her health and safety duties in a practical sense. This ambiguity is not confined to Ireland and also arises in the international context. However, several other common law jurisdictions have taken steps to try to address the problem. For example, in an attempt to clarify the WHS obligations imposed on directors, countries such as Australia and New Zealand have introduced legislation[2] that imposes a positive duty on company directors[3] to exercise “due diligence” in order to ensure that an entity complies with its WHS obligations. Although the legislation in these jurisdictions hasn’t gone so far as to provide complete clarity for duty holders[4], the due diligence criteria provide a useful starting point for Irish directors who are negotiating their personal WHS duties.

What is health and safety due diligence?

The term ‘due diligence’ is often associated with corporate mergers and take-overs. In many jurisdictions, the concept of due diligence in the safety context is still quite novel. However, the WHS legislation in New Zealand and most States and Territories in Australia currently requires company directors to exercise due diligence by taking reasonable steps to:

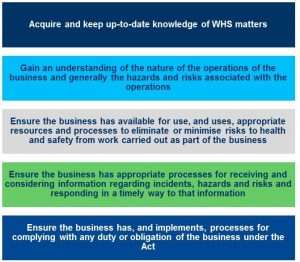

(a) acquire and keep up‑to‑date knowledge of work health and safety matters; and

(b) gain an understanding of the nature of the operations of the business or undertaking of the person conducting the business or undertaking and generally of the hazards and risks associated with those operations; and

(c) ensure that the person conducting the business or undertaking has available for use, and uses, appropriate resources and processes to eliminate or minimise risks to health and safety from work carried out as part of the conduct of the business or undertaking; and

(d) ensure that the person conducting the business or undertaking has appropriate processes for receiving and considering information regarding incidents, hazards and risks and responding in a timely way to that information; and

(e) ensure that the person conducting the business or undertaking has, and implements, processes for complying with any duty or obligation of the person conducting the business or undertaking under this Act[5]; and

(f) verify the provision and use of the resources and processes referred to in paragraphs (c) to (e).

Summary – synthesis and implementation

The steps listed above cannot be followed in isolation. It is the cumulative effect of planning, learning, reviewing and revising that amounts to effective workplace health and safety management.

![]()

It is well known that health and safety duties imposed on companies and on individual directors are onerous. It is also common knowledge that a breach of any one of those duties can lead to serious penalties. Until legislation is revised to clearly inform Ireland’s company directors of the practical requirements embedded in their WHS duties, taking guidance from fellow common law countries[6] seems like a valuable and worthwhile step to include in any director’s personal due diligence arrangements.

About the author: Aoife is an Irish and Australian qualified employment and safety lawyer. Aoife specialises in defending companies and senior executives in health and safety prosecutions, managing regulatory investigations and providing front end safety advice.

[1] Including imprisonment, fines of up to €3 million and disqualification from holding a directorship.

[2] In 2011, the majority of States in Australia adopted a set of model set of work health and safety laws. Some states remain governed by state-specific legislation in the safety context. Similarly, in 2016, New Zealand introduced the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015). This Act is based on the model laws introduced in Australia and was adopted and implemented following a review of worldwide standards.

[3] And other “officers” of the business who participate in the making of decisions that affect the whole, or a substantial part of, the business and a person who has the capacity to significantly affect the financial standing of an organisation.

[4] And although not legally binding in the Irish context.

[5] Examples: For the purposes of paragraph (e), the duties or obligations may include reporting notifiable incidents, consulting with workers, ensuring compliance with notices issued under the legislation, ensuring the provision of training and instruction to workers about work health and safety, ensuring that health and safety representatives receive their entitlements to training.

[6] Where the nature of dominant industries such as mining and long-distance transport have created a highly regulated WHS environment.